I’ve created “courses” at LinkedIn Learning since 2008, when the company was called Lynda.com. Lynda.com was one of the earliest, if not the first, video training companies out there.

Their course format is a series of short videos. One video segment may lead into another, but fundamentally, each segment stands alone as a unit. After (theoretically) watching the videos, you receive a certificate of completion which you may attached to your LinkedIn profile.

Theoretically, because you can get this certificate simply by streaming the videos in the background, on mute.

Theoretically, because there’s no transference of skills happening to one’s own projects or situation, no reflection on the learning process, nor is there a meaningful evaluation of learning for either the learner or the instructor. LinkedIn Learning is aware of this issue and they continue to work on ways to solve it.

However, the genie is out of the bottle, so to speak. The LinkedIn Learning “course” has become a misnomer that others try to emulate.

Photo by Karolina Grabowska from Pexels

This is not a course

In the explosion of online courses offered all over the internet, a “course” is now a series of videos hidden behind a login. Pay your money and get a handful of overproduced videos that cover your area of interest.

Then the creators wonder why students aren’t learning the material, or wondering why sales have dropped. Currently, creators turn to more bells and whistles in the videos, more animation, more attempts to make “edutainment” rather than solid education.

Even if your course is an asynchronous, instructor-absent course, where students move through it at their own pace, you need more than video to truly make a course.

When videos become a course

Videos are awesome for demonstrating something. However, they’re terrible for transferring knowledge to a new environment. They’re not good for measuring what you’ve learned. Consider how often you watched someone do something and you think, “that doesn’t look so hard.” Then you try it, and you quickly discover that you have no idea what you’re doing.

Yes, have videos in your course. No, videos aren’t the whole course. You need more to round out the learning experience. Here’s some suggestions.

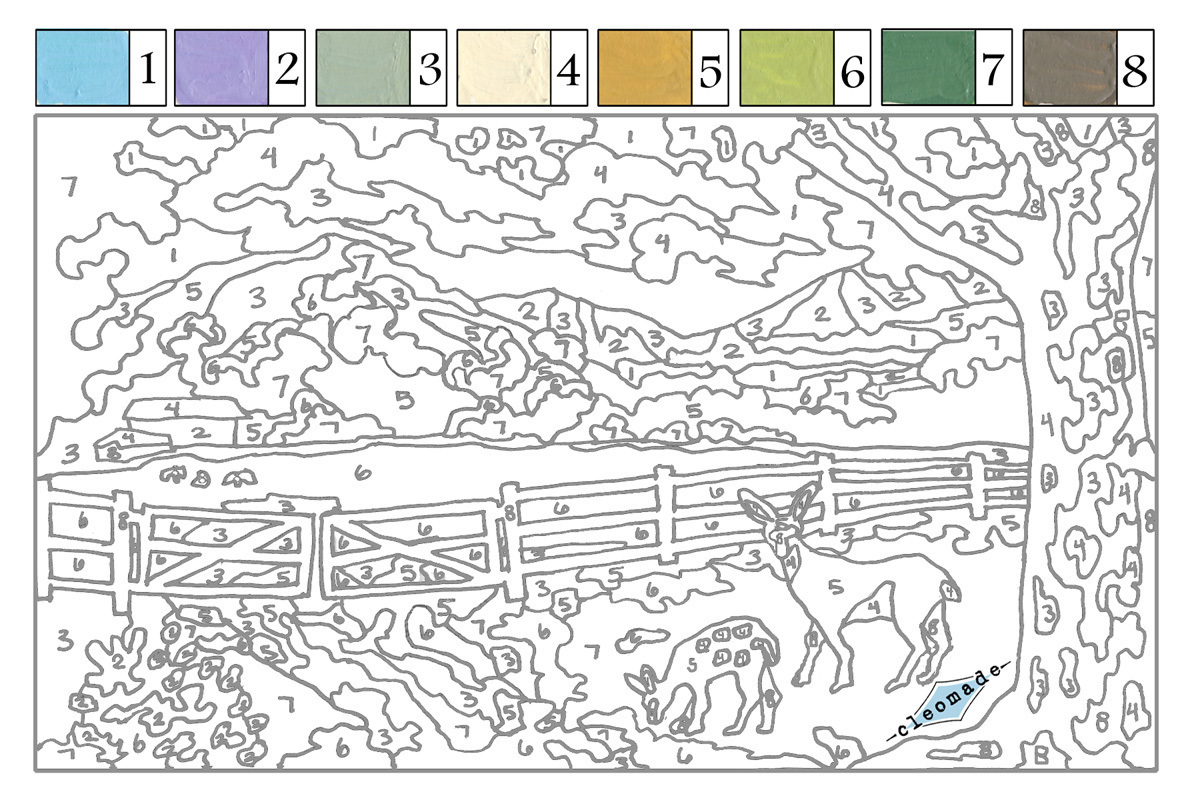

Quizzes and games

Add self-graded quizzes to evaluate student’s assimilation of the video. These don’t have to be standard-issue multiple choice. Consider matching games, categorization games, and formats that involve photos, not just words. This type of evaluation is best for terminology or other behaviorist “you just gotta know this” material.

I do it, we do it, you do it

In your video, demonstrate how to do the thing you’re teaching. Ideally, students are following along with you, doing the same thing.

Now provide your students with the assets they need to do the same type of thing on their own. You provide the structure to think about the problem, the goal they’re trying to achieve, and any boundaries and guidelines for where they should focus their attention. Follow this up with a video explaining how you solved the problem. Bonus: have a discussion thread where students may post photos or links to their work, along with a brief reflection – what went well? Where did they get stuck? What do they still not understand? What would they do differently next time?

Finally, invite the students to do the thing on their own. Provide a separate discussion thread where they can show off their work. Again, encourage reflection, not just “this is my thing.”

The middle step is the most important, because this is when transference happens. By giving them a small project with everything they need to succeed, this is where students gain confidence or realize they need more help in a certain area. They get a sense of what’s required to do the thing on their own.

Incidentally, the middle step is the piece that’s missing in almost every course out there. It’s definitely missing in every software course. And it’s super critical for understanding how to program.

Workbooks provide structure

When students learn something new, they’re not only learning the buttons to click, or the syntax, or the structure. They are also learning the organizational tools and thinking processes that go with the thing they’re learning.

This is one of the most overlooked aspects of teaching. Students of all abilities and intelligence have an issue with this. My Harvard students had as difficult a time knowing where to start a project as students did at any other university where I’ve taught.

Give people a structure for thinking about the problem at hand. If it’s a 5-step process, the workbook contains those 5 steps written out, along with whatever questions they should address and a space to write. Include reflection questions. Include suggestions for making the activity more challenging or less challenging.

Surprisingly, even in our digital age, people do not mind printing a workbook and writing all over it. In fact, many prefer this methodology, because they feel like they have a tangible asset after class is done.

Hopefully some or all of these tips help you raise your online video series to a full course.

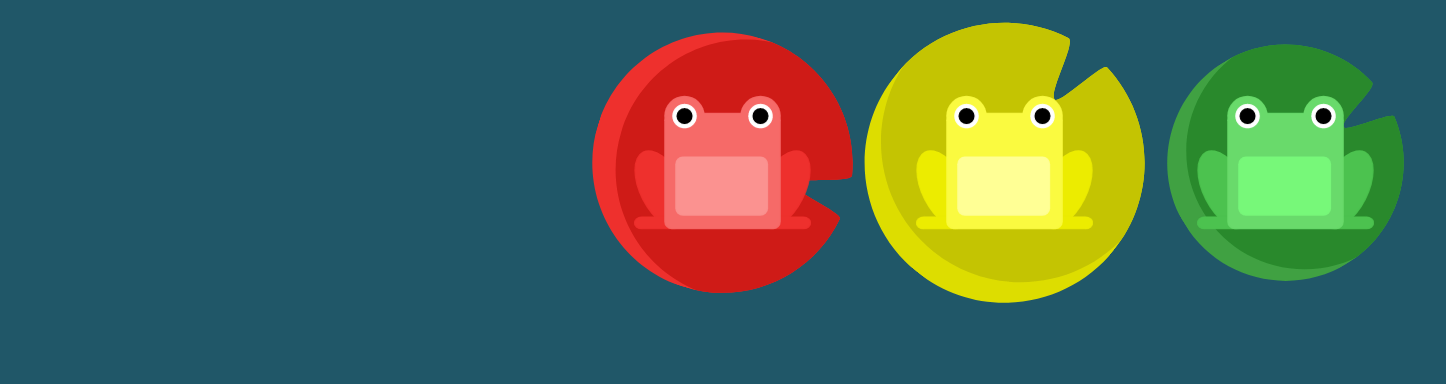

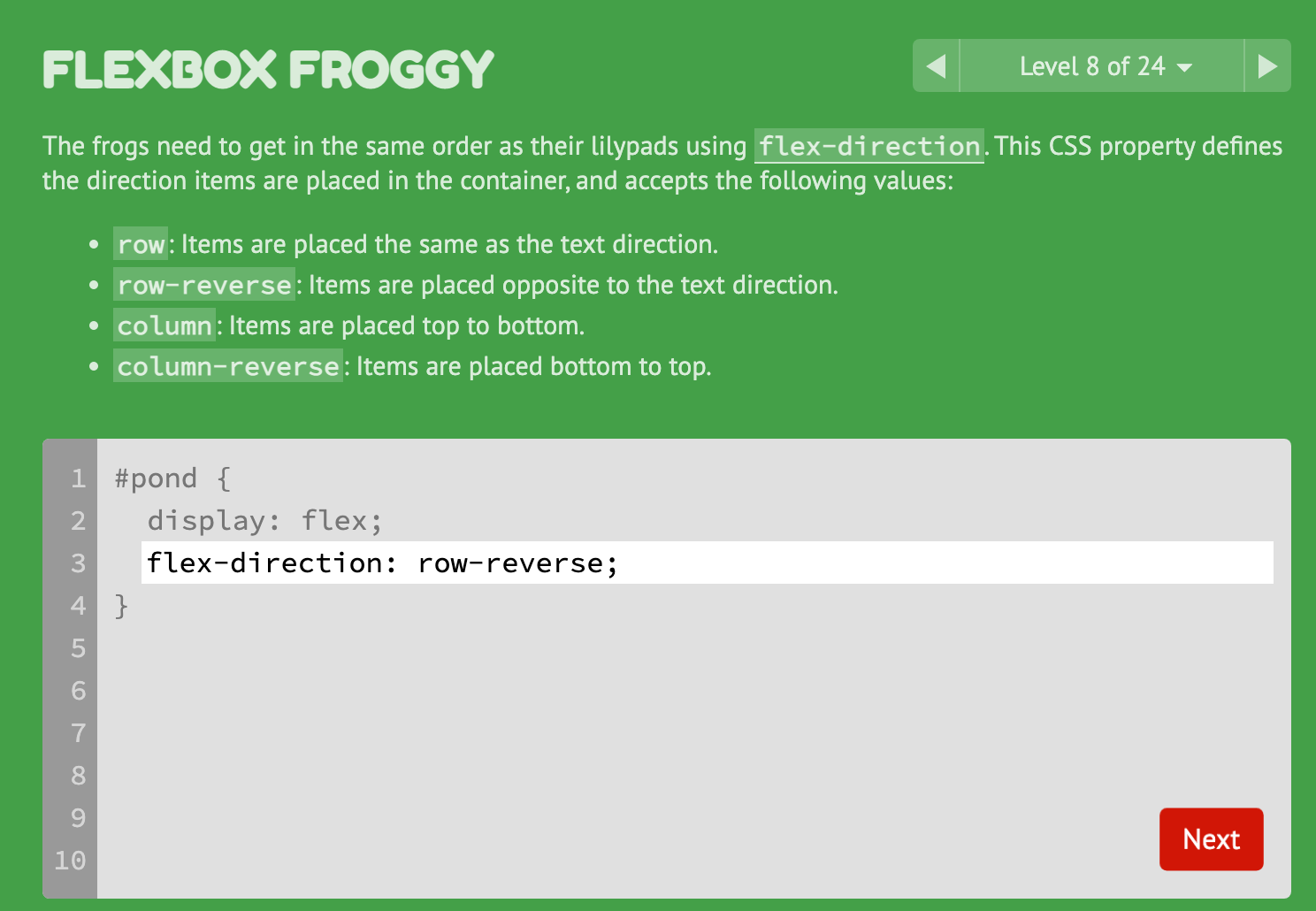

Level 8: Frogs are not quite aligned with their lilypads to start.

Level 8: Frogs are not quite aligned with their lilypads to start.

After typing in the appropriate Flexbox CSS properties and values, the frogs align to their lilypads. Adorable.

After typing in the appropriate Flexbox CSS properties and values, the frogs align to their lilypads. Adorable.

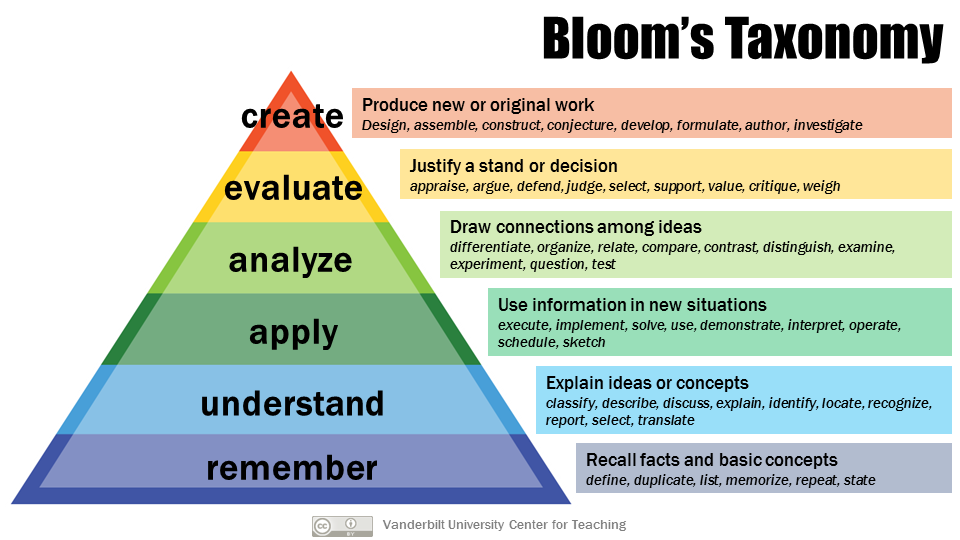

Armstrong, P. (2010). Bloom’s Taxonomy. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved October 28, 2022, from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/.

Armstrong, P. (2010). Bloom’s Taxonomy. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved October 28, 2022, from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/.