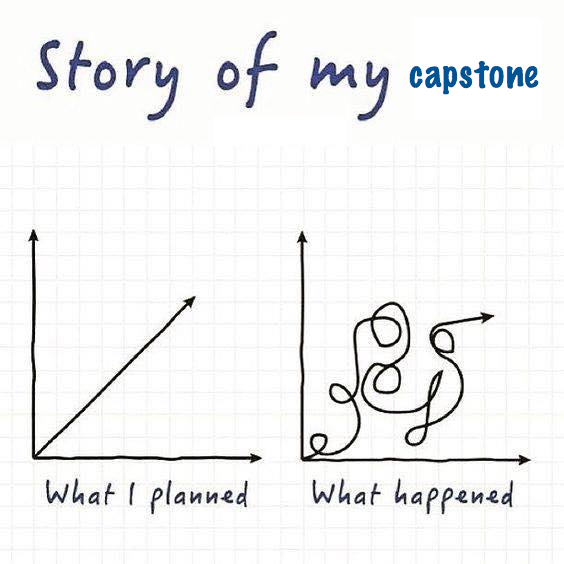

Capstone projects are all unique. Harvard’s digital media capstone projects are all over the map: films, courses, websites, UX projects, and combinations of these.

It is impossible to structure grading for a capstone project for this reason. However, structured grading is most vital for this course among all others.

In every other university course, grading happens during the term in some way through periodic assignments. Even in courses with a heavy assignment at end of the course, students still have some concept of how they’re doing as they complete their final work.

However, a capstone should be evaluated as a complete work, rather than evaluated piecemeal through the term. While students should get feedback along the way, they shouldn’t receive a hard grade until the end. They should have the opportunity to refine all deliverables and aspects of the project in light of whatever they’re currently creating. The point of capstone is to bring together multiple aspects of the degree program and synthesize learning over the curriculum. Grading, therefore, needs to be at the end and encompass the full project.

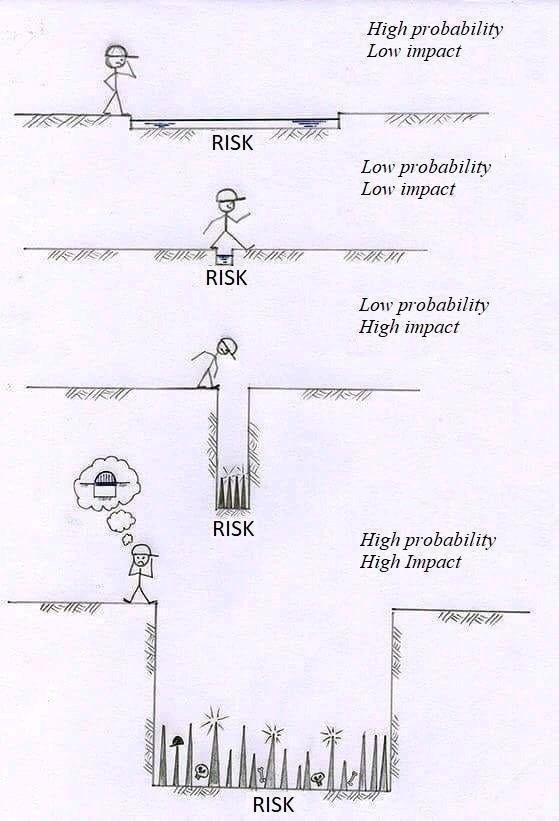

This clearly leads to potential issues. What happens when the student thinks they’ve done A work, but the instructor thinks it’s a C-? What happens when the student’s project isn’t “weighty” enough for a capstone? These potential surprises (risks!) must be mitigated in some way.

As I’ve mentioned in a previous post, students don’t understand mitigating risk going into capstone, nor do they understand how to scope a project. We also have an issue of how to grade a unique project.

Fortunately, a student-written grading rubric solves all of these issues.

I review their rubric and make sure the bar isn’t set low or that they’re working on trivial things. But have faith in these adult students. They chose to go to grad school with a reason in mind. Most want to do well on their project, but they also want to learn something new and be proud of their work. With guidance, they write a challenging rubric that stretches them, but not too far so it’s still achievable within the semester timeline.

Let’s go through all of the learning that happens when students write their own grading rubrics.

Rubrics identify deliverables and completion timelines

It’s one thing to say “I’m creating a 15-minute documentary on X topic.” It’s another to spell out exactly what it takes to create that: storyboarding, running the interviews, choosing the B-roll and music, editing it together.

Larger deliverables may be broken down further. For example, an interview segment might be graded according to lighting, camera angle and focus, sound quality, color correction, how it furthers the story, and consistency of these characteristics across interview segments.

Most students also put together a timeline for their work along with this list. I encourage them to create milestones, so they can quickly measure if they’re on track, behind, or ahead of schedule.

When students write down all of the elements and stages they must complete to create their project, and particularly once they schedule these over the semester, they start to get a sense of scope. They realize whether they’ve committed to too much work and need to scale it.

Rubrics determine how work should be weighted and graded

Once students have completed their list of deliverables, the next question is how to grade each deliverable.

There are two parts to this question. First, how do we evaluate each deliverable? Second, not all deliverables are created equal, so where should we place grading emphasis, and what should be minimized?

Grading

My students and I have conversations about how to communicate grading so that we’re both on the same page. How do you define good quality in a rubric so it’s clear enough to hang your grade on it?

Still, my favorite rubric item shows up over and over, year after year: “The website will be simple and easy to use."

A noble goal! But how do we measure that? What is simple and easy for you may not be for me. This is usually where I ask the student if they will do user testing to ensure the site is simple and easy to use. And if the testers show that it’s not, what will they do then? (Usually this is sufficent to convince them to refine this criterion in some way to reflect the intent, but in a more measurable way.)

Students struggle with quality metrics in rubrics, but in the end, it’s a good exercise. It’s part of learning clear communication. It’s also useful for the end of the course, when they’re running out of time and they’re paralyzed by whether something is “good enough.” Since they made the decision of how to measure their work up front, allocating their time is an easier decision.

Weighting

Some deliverables are more important than others. Some should be completed at a different level than others.

If a student is creating a documentary as their main focus, and they want to also complete a website for that documentary, I think that’s great. But the website is a minor deliverable. It might be built with Squarespace or other no-code technology.

If a student is creating a website as their main focus, however, it’s not going to be built in Squarespace, and it will involve some level of coding.

Within a deliverable, elements may be weighted differently as well. With websites, for example, some students want to emphasize graphic design, or page performance, or writing some type of code, or usability. All of these are important to the site, but not all need to be emphasized in the capstone project with a limited timeline. An ugly website with innovative coding may be as legitimate a project as a website with breathtaking graphics and photos and less coding.

Students should have some say in what they consider important (and presumably where they want to spend their time), vs. what they consider less important. I ask students to reflect on their learning goals for this project, in addition to the amount of time required for each deliverable. Those that take more time might be worth more points. There may be some “stretch deliverables” that the student isn’t confident they can reach, but they don’t want to jeopardize their grade or graduation. These might be weighted less to help mitigate risk.

Likewise, when students identify trivial deliverables (“navigation will work on all pages of the website”), I gently point out if they have not mastered navigation bars prior to enrolling in capstone, they are not qualified to build a website as a capstone project.

Rubrics for time management

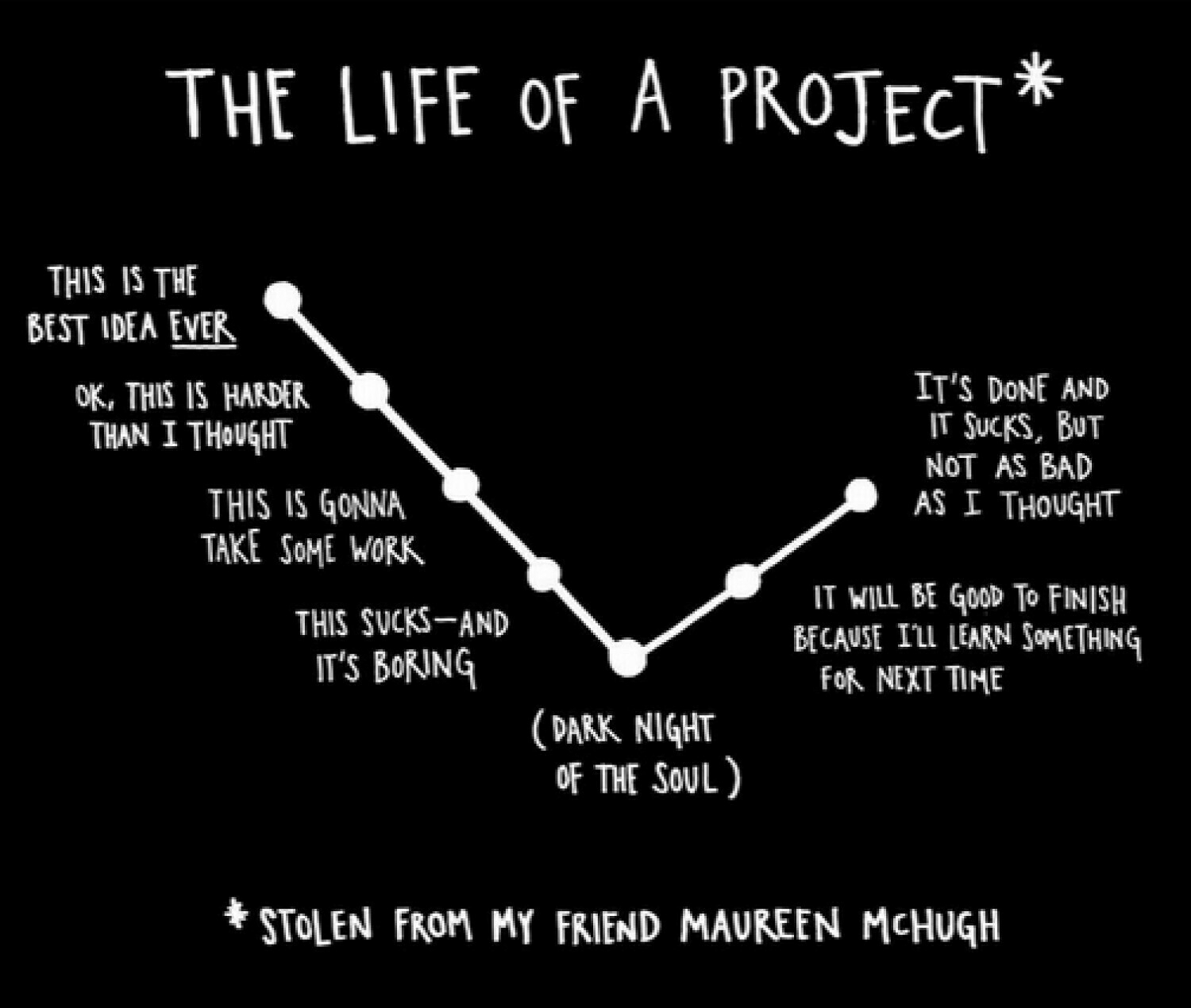

In the last 4 weeks of the semester, as the students are in their final grind to complete their projects, inevitably some level of panic sets in. Some deliverables took longer than expected. Work was demanding. Home life is demanding, particularly in pandemic times. Life happened along the way.

I remember when one student discovered a new technique for coding his project in these final weeks. He asked if he needed to refactor his project to use the technique. I asked what was on his rubric. Since neither the technique nor refactoring was listed as a deliverable, he understood he should keep going with what he had. Refactoring could be done after capstone.

Other students are short on time but long on deliverables towards the end. I advise working on deliverables with heavier weighting. They can also decide what’s faster and easier to complete and concentrate efforts there.

Rubrics for organizing deliverables

“Here’s my film!” Great! Now what?

I have students use their rubric as an organization tool for their deliverables. Where should I look for proof of excellence in each criterion?

Not all deliverables are contained within the main project (film, website, course). For example, a storyboard is critical to the film, but it’s a separate deliverable from the film. Many website and course deliverables also follow this pattern.

Rather than being forced to hunt for All The Things, students choose where I look. Time stamps, website addresses, lines of code, Word documents, and more form the basis of deliverables.

Rubrics for reflection

Finally, students fill out their own grading rubric as part of the reflection process. (I also ask them to write a final blog post reflecting on what went well and what they’d do differently next time.)

When students grade themselves, they are required to compare their work with the measurements they set. Did they achieve these metrics? Why or why not?

In most instances, students gave themselves lower marks than I did, sometimes dramatically so. The rest of the time, I agreed with their assessment. I can only think of one instance where my grade was lower than the student’s.

Many students start this grading and reflection exercise with an eye roll, believing it’s the final busy-work hurdle to graduation. But I don’t give busy work. By the time they’re done, they usually comment on how useful the reflection process was.

Whew, that’s a lot for one grading rubric. If you wind up with capstone students, I strongly recommend trying it with your next cohort.

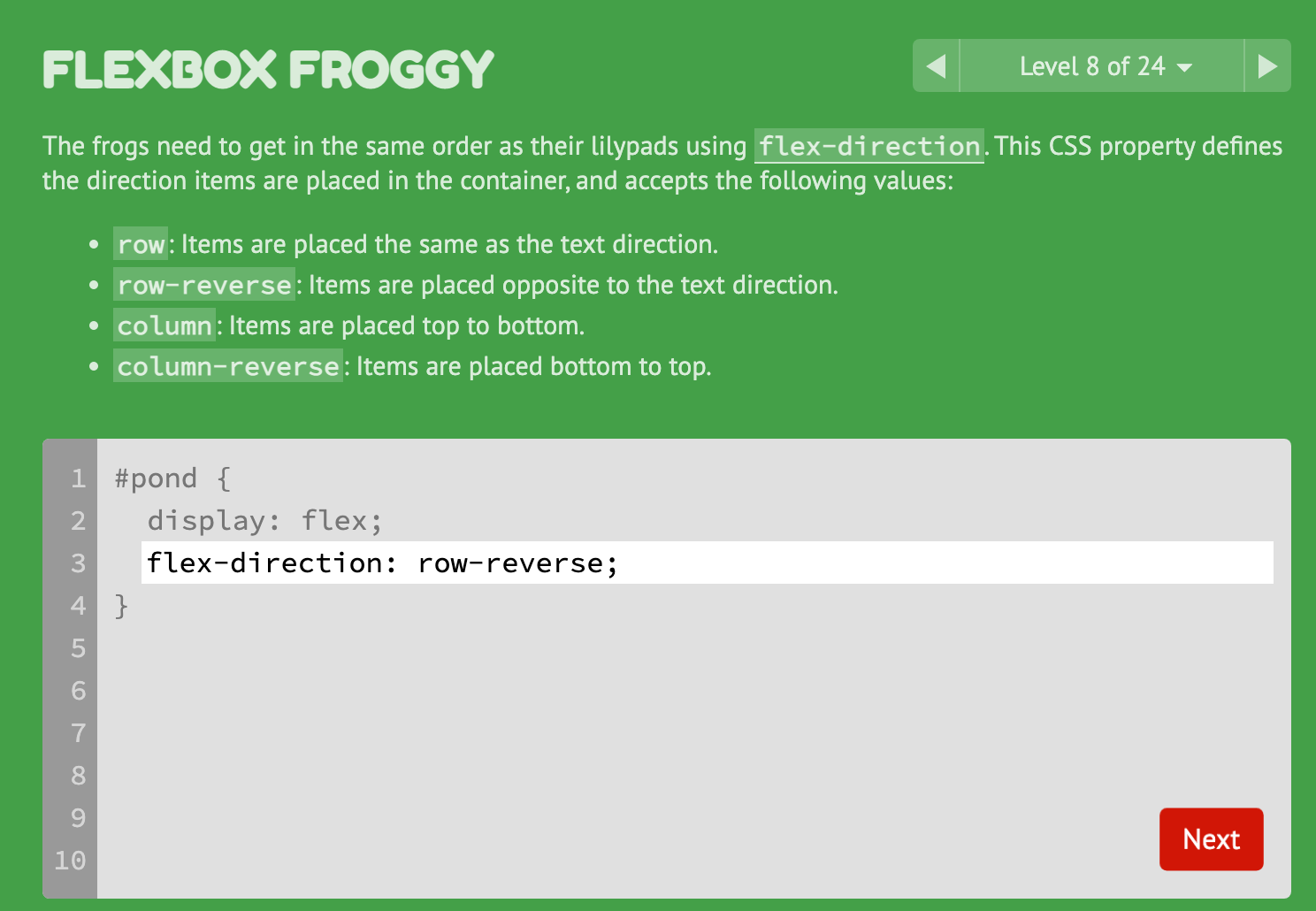

Level 8: Frogs are not quite aligned with their lilypads to start.

Level 8: Frogs are not quite aligned with their lilypads to start.

After typing in the appropriate Flexbox CSS properties and values, the frogs align to their lilypads. Adorable.

After typing in the appropriate Flexbox CSS properties and values, the frogs align to their lilypads. Adorable.

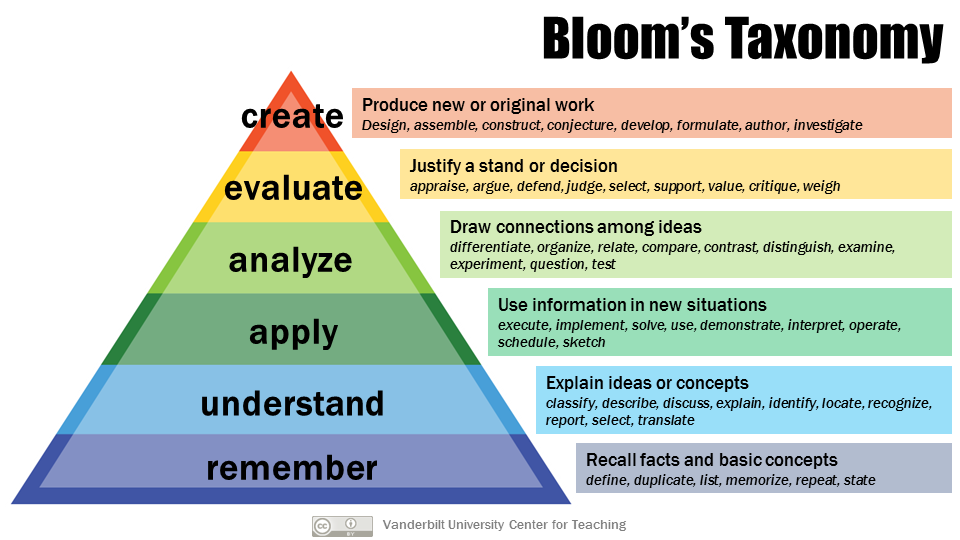

Armstrong, P. (2010). Bloom’s Taxonomy. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved October 28, 2022, from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/.

Armstrong, P. (2010). Bloom’s Taxonomy. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved October 28, 2022, from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/.