After 20 years of teaching in academia, I’ve coached many capstone projects.

Part of the capstone process is examining risk and mitigating it. Students have very little ability to do this, even after completing courses and assignments for a full degree program. This is because in a regular course, the instructor assigns all materials to consume and study and provides assignment(s) that have deadlines. Students manage time and scope based on work that’s already defined these parameters for them.

That means that when a student is creating a project of their own, they do not understand how to properly scope their work within the time parameters.

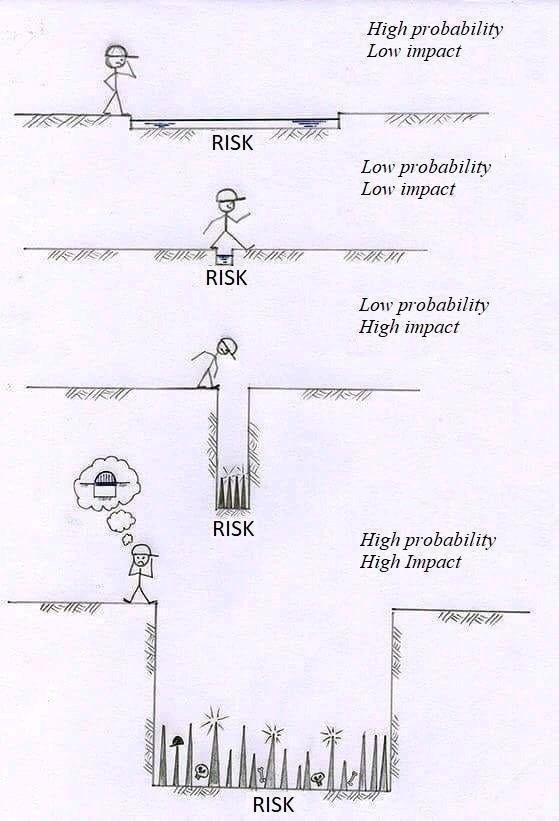

They also don’t understand risk. In a standard university course, risk during the semester usually looks like this for adult students with jobs and lives:

-

High probability, low impact: Work or kids get demanding during a portion of the course. Work ahead, talk to the instructor, and usually you get through this without significant damage to the grade.

-

Low probability, low impact: Not completing a weekly requirement: not attending class, not completing a weekly quiz, not posting a discussion post. This could be simply forgetting something, or it could be a conflict with other parts of life meant that the work just didn’t get done.

-

Low probability, high impact: Death in the family, severe illness of the student or in the student’s family, childbirth during the term. Universities have methods of working around these issues via course incompletes. Students should always talk to instructors to get help when these issues happen.

-

High probability, high impact: There are certain students who are consistently bad at managing time and always seem to have some drama going on. If you talk to other instructors who had this student previously, you’ll discover the pattern across all courses. However, these students are rare in adult learning programs.

In other words, while students are always concerned about getting a lower grade than they think is reasonable for their work, talking to the instructor consistently and being engaged in the course is generally enough to get through it.

For a capstone project, they are concerned about failing the project and jeopardizing graduation. Low probability, high impact. However, when the student controls most of the project, as is true for most parameters of capstone, the probability is higher here than it is for other courses. Students don’t understand how to scope their work – a topic for another post – and can easily sign up for too much to complete within the allotted time. This is the biggest reason that capstones would not be completed.

How to mitigate this risk? Focus on what’s needed for the project to get to graduation.

Consider the metaphor of visiting an all-you-can-eat buffet the first time. It’s amazing! There’s so much food! You can eat whatever you want and they bring more! But pretty soon you’ve tried a few things, and you’re getting full. You didn’t get to dessert yet because you ate too many dinner rolls.

Students in a healthy relationship with their capstone project have similar issues. They want to do ALL THE THINGS and make an amazing project. They identify more things along the way that they want to do. All the while, the clock is counting down. While the student may believe all of the things are required to make a good project for a portfolio, it’s unlikely that they’re all required to complete capstone satisfactorily and graduate.

(Students in an unhealthy relationship with their capstone project do the absolute minimum. It’s rare, but it does happen occasionally. Usually this is affected by outside forces – illness, death, other life issues. The student may also have chosen a poor project that isn’t engaging for them. That’s for another post.)

As an instructor, you must teach them about the low probability, high impact problem of not doing the right things for graduation. Graduation is always goal #1. Everything else is Phase 2.

One of the ways I’ve kept students on track to completing their capstones is through a grading rubric. This is also suited to another post, but briefly, a rubric identifies what they will do, how important that work is, and how it should be graded. It’s a contract of sorts.

Future posts:

-

The power of the student-written grading rubric in capstone

-

Scoping capstone projects and keeping students in scope

-

Helping students choose engaging capstone projects